Ancient quarries and lithic exchange networks in eastern Africa

Prehistoric East African Quarry Survey (PEAQS)

Quarry debris from the Elmenteitan Obsidian Quarry site on Mt. Eburru, southern Kenya.

PEAQS: Goals

The Prehistoric East African Quarry Survey is an archaeological project aimed at understanding how ancient peoples integrated the access and use of stone sources into economic & social systems. I study quarry sites across Kenya and Tanzania to reconstruct lithic production sequences, land-tenure systems, and raw material exchange networks.

PEAQ's major goal is to investigate how the role of quarries in ancient cultures changed during the transition from hunting and gathering to food production in eastern Africa.

Quarry archaeology

Before the advent of metallurgy, human beings around the world relied heavily on stone tools for activities like hunting, preparing hides, cutting, working wood, bone, and leather, and drilling. Only certain raw materials have properties that allow them to be predictably "chipped" or "knapped" into specific shapes with sharp edges. High quality materials like obsidian (volcanic glass) or chert only occur in specific places on the landscape. Natural sources of high quality stone quickly became important places on the landscape for prehistoric groups, who had to develop strategies to maintain regular access to good knappable stone while also balancing basic subsistence and cultural concerns. Regular visits to these sources to mine stone, test nodules, and prepare lithic cores for easier transportation, resulted in dense accumulations of stone debris. These "quarry" sites are rich sources for information about stone tool production techniques, and core-preparation sequences. In addition to the variation in these strategies, the spatial organization of activity areas and other lines of archaeological evidence offer important clues as to the broader structure of the lithic economies of the populations using these sites. In other words, a quarry is a concentrated picture of broader lithic technological organization.

Quarries are not only important for reconstructing stone tool economies. As important places on the landscape that are regularly re-visited, they often take on social and cultural importance. Archaeological investigations of quarries also provide opportunities to understand how prehistoric societies organized things like access to resources and land-rights, raw material exchange networks, and social alliance systems.

“Quarry archaeology is the

logical start to the study of any

stone tool using culture”

Research in Kenya

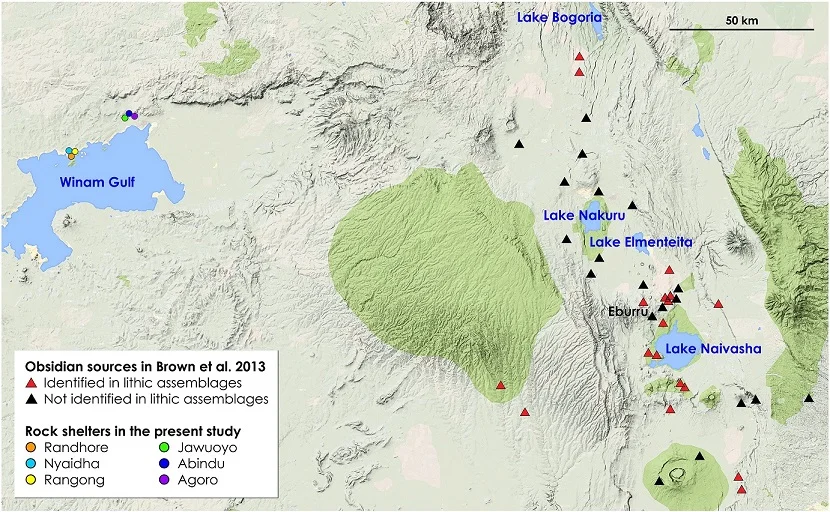

PEAQS has been so far focused primarily on obsidian quarry sites in the Central Rift Valley of southwestern Kenya. This grew out of my dissertation research on major quarry sites on Mt. Eburru and Lake Naivasha that were preferentially used by early herding societies that migrated into the region between 3200-1500 years ago. Excavations have been focused on the Elmenteitan Obsidian Quarry that served as an economic and social nexus for producers of the Elmenteitan pastoralist culture group. I have also surveyed several obsidian quarry sites used by other early pastoralist groups and by diverse Holocene hunter-gatherer groups. My research is demonstrating that during the transition to food production, use of quarries became more controlled and organized in order to supply new regional exchange and distribution systems. These systems likely became important for maintaining social networks between early herders who relied on cooperation and exchange partnerships to survive periods of drought, raiding, or livestock epidemics.

Other research areas include the Lake Turkana Basin, where I am working with the Later Prehistory of West Turkana project to understand the switch from local to exotic stone sources during a period of dramatic climatic and cultural change from 5000-4000 years ago. I am also working with the Research on Ancient Pastoralism in Tanzania project to investigate how the preference for very local but low quality stone by the earliest pastoralists in north-central Tanzania factors into the novel strategies of economic resilience pioneering herders developed in frontier environments. Finally, I am working with ongoing obsidian geochemical sourcing projects to reconstruct shifting exchange relationships and social networks between foragers and food producers in various regions of eastern Africa.

Archaeological Research on Ol Doinyo Opuru (Mt. Eburru) in southwestern Kenya.

The distinctive upper slopes of the Mt. Eburru volcano. This high altitude environment hosts several archaeological important obsidian quarry sites.

In my investigation of the Elmenteitan Obsidian Quarry site I used multiple lines of evidence to address my research questions, with an emphasis on the study of stone tool technologies as the most enduring and abundant facets of the archaeological record. This is especially relevant for the study of prehistoric herders in Kenya, who developed long distance exchange networks to transport high quality obsidian from specific geochemical source groups to widely disperse communities from c. 3000-1400 years ago. My study of the material signatures produced by tool production, use, and disposal allows me to trace the structure of these exchange networks across the landscape. At the center of these networks, is a central obsidian quarry site on top of Ol Doinyo Opuru in the Central Rift Valley, north of Lake Naivasha, which was used exclusively by a single pastoralist culture-group for over 1500 years. “Ol Doinyo Opuru” translates as “The Mountain of Steam”, and is a geochemically active volcanic complex with distinct green obsidian outcrops on the upper slopes, in what would have been a remote forested area.

With the goal of understanding the role of this important node within the exchange networks I study, I undertook the first surveys and excavations of the quarry site in the late Summer/ early Fall of 2014. In collaboration with colleagues from the National Museums of Kenya, we identified spatial activity patterns and material traces that indicate that communal participation in lithic reduction at the Opuru quarry site was actually a vital means of organizing exchange networks, and building the social alliances to maintain them across the region. In addition, the tremendous amount of stone tool debris we recovered spans over a millennium of consistent use, and is an invaluable data set for identifying changes in technological responses to social and environmental stress. When the data from these excavations is combined with datasets from sites excavated over the last 50 years, it offers a unique opportunity to understand how herders were organizing strategies through both time and space. This offers a critical new perspective in anthropological discussions of how food production spread and was maintained in African contexts.

Surveys in the high-altitude Mt. Eburru Forest Reserve

In 2014 I partnered with Kenya Wildlife Service and the community of Eburru Center to conduct walking surveys of the dense montane forests on the highest slopes of Mt. Eburru. We identified several rockshelter and cave sites in this environment, which was historically used by the Ogiek hunter-gatherers. We were joined by community elder Mr. John Kimani who practices herbal medicine and identified several species of medicinal plants that grow in this highland environment.

Quarry surveys in the Lake Naivasha Basin

The 2014 Research Team. Back row from left to right - Francis Nduulu Mutua, John Kimani, John Munyiri, F. N'yany'a. Front, left to right- Steve Goldstein, M. Kukenga.