Human impacts on savanna environments

Archaeology of human impacts on African savanna ecosystems

The stereotypical African rainforest and savanna environments.

We typically think of these as "natural", however archaeology and ecological science are revealing that the nature and extent of Africa's diverse ecology has been shaped by thousands of years of human land-use practices.

An Anthropogenic Africa

We can think of hominids' and early Homo sapiens' relationships with African ecosystems as "co-evolutionary". Predator-prey relationships and resource distributions shaped our own adaptions as much as our hunting and gathering lifeways affected the environments in which we lived and the animal species with whom we interacted. These relationships began in magnitude over the last 100,000 years as we began developing strategies like bow-and-arrow hunting and intensive fishing/marine resource exploitation. New tools and technologies allowed us to affect selection and population size for a much broader range of fauna, potentially to a much greater degree than before. One of the biggest changes in human relationships to the "natural" world came around 8,000 years ago, when African populations began adopting lifeways based on herding domesticated species of cattle, sheep, and goat. This was eventually followed by the domestication of African plant species like sorghum and millet. As humans transitioned from hunting and gathering to food production, the ways they used the landscape were fundamentally altered.

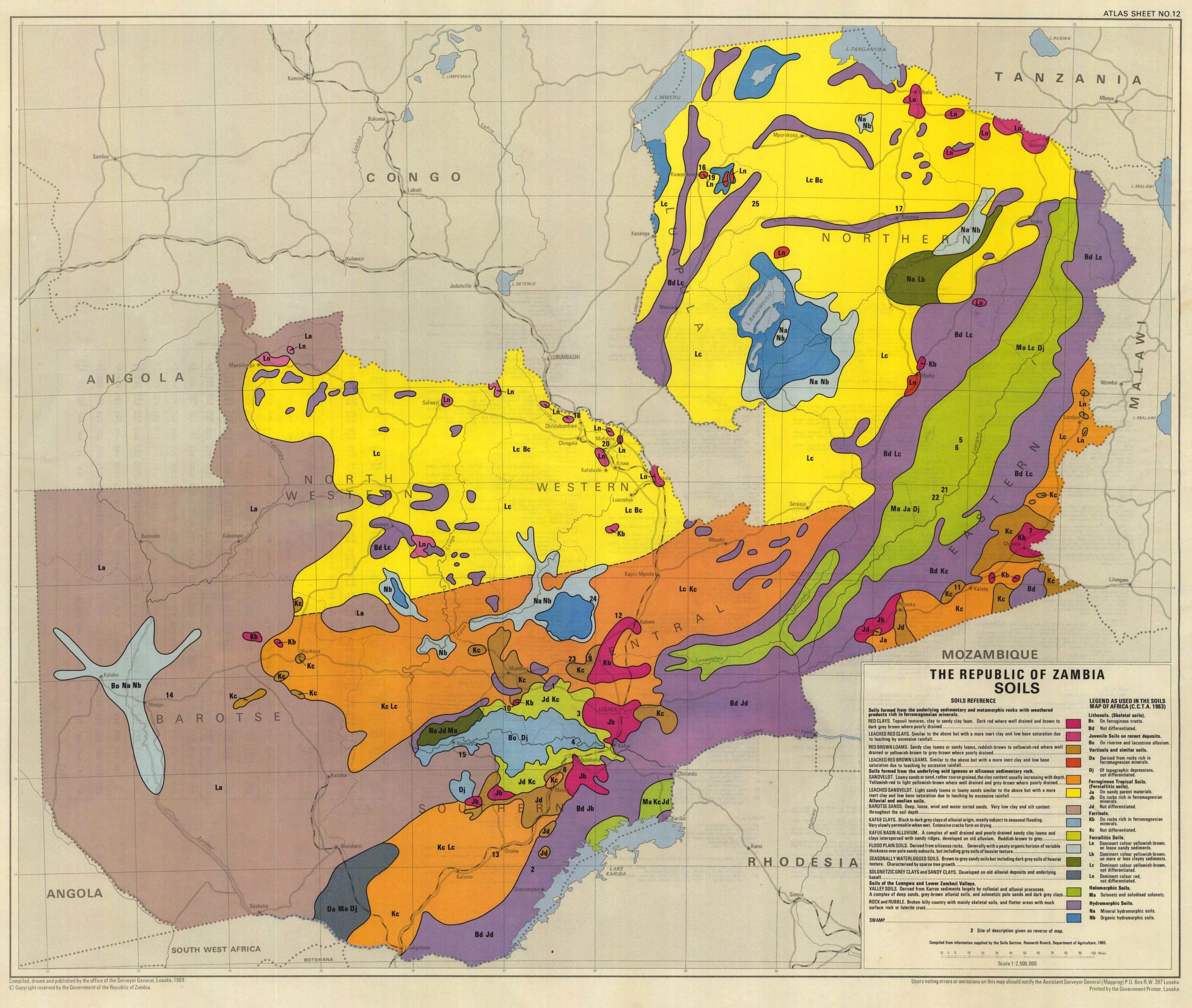

The origin and spread of food producing lifeways forever altered environments across African. Herding populations dispered from the Sahara throughout eastern and southern Africa from c. 6000-1000 years ago, becoming one of the dominant lifeways on the continent. Domesticated bovids consume grasses and other vegetation, transforming it into meat and milk that humans can consume. Unlike wild ungulates herds, domesticated herds were managed by people who decided where they would graze. Early herders spread during a period of major climate change, and cycles of high and low rainfall Where and when people moved their herds had major implications for vegetation succession and ecological development during this new climatic period. In other words, the impacts of grazing altered the trajectories of many savanna grasslands. Herders are portrayed negatively as a cause of livestock overgrazing and erosion. Research with contemporary herders is showing that they actually use complex land-use classification systems to prevent over-grazing (Oba and Kaitira 2006). By keeping livestock in enclosures at night, both modern and historical herders created large accumulations of nutrient-rich animal dung that enhanced soil productivity around their settlements (Boles and Lane 2016). These concentrated nutrient "hotspots" promote the growth of higher quality grasses, that in turn attract wild and domesticated animals. The cumulative effects of this process has substantially altered the composition of grassland environments. Herders also regularly burn bushland to promote more open grasslands for grazing and to reduce the risk of tsetse fly born livestock disease. But do these land use practices extend further in time than the last few hundred years? If so, thousands of years of pastoralist landuse has likely engineered the savanna grasslands as we know them today.

The spread of iron technology also played an important role in reshaping sub-Saharan Africa. Iron production requires large amounts of charcoal, and in many parts of the world the intensification of metallurgy led to significant deforestation. Iron tools aided farming lifeways, making it easier to transform additional forest or grassland into agricultural fields. Such major changes to the extent and distribution of forests, the proliferation of new plant species, and increased iron production would have not only affected local environments, but may have contributed to early anthropogenic climate change.

The timing and extent of these processes in Africa are poorly understood. Archaeological evidence suggests iron technology spread along with farming economies from central Africa into southeastern Africa by 1500 years ago- and earlier in some regions. Evidence for the early Iron Age in eastern Africa is sparse, however Zambia and Botswana offer a rich archaeological record for the growth of iron using farming societies.

Poster presented at the 2017 Society of American Archaeology conference in Vancouver, Canada.