Experimental archaeology and lithic analysis

Experimental and replicative archaeology

Obsidian handaxes made by S Goldstein in Naivasha, Kenya.

Using traditional methods to replicate ancient tools adds critical insight into ancient cognitive and technological processes. We can also treat replication efforts as scientific experiments, wherein we can control certain variables to see their affect on the outcomes. Archaeologists observe and measure the kinds of debris from production processes so that we can better identify different production strategies from the refuse left behind in the archaeological record. We also conduct experiments to evaluate tool use and function. By using tools we are able to see how they break, how often they need to be repaired or modified, and how different aspects of shape or size might change through their use-life. These methods help us to understand the practical reasons why ancient peoples made certain choices about raw material, tool shape, or tool manufacture process.

Experimental archaeology is a cornerstone method in archaeological science, and is a major theme of my own research on the stone tool technologies of eastern Africa. During the Pastoral Neolithic period (~3200-1500 years ago), there was a diverse mix of herder and hunter-gatherer societies co-existing and interacting across the landscape. Nearly all of these groups relied on classically "Later Stone Age" stone tool technologies, which focus on the production of elongate stone blades, backed geometric pieces, stone hidescrapers, and diverse "microlithic" implements. At first glance all LSA toolkits may look the same, but closer analysis shows variation in the form, size, or frequency of different kinds of tools. Is this variation between groups stylistic, symbolizing group identity, or does it have a functional basis that reflects fundamental economic differences between groups? I investigate these questions by replicating and using different tools.

I have over 10 years of flintknapping experience, and extensive experience in replicating ancient projectiles, and butchery/hide processing with stone tools. Beyond my research in East Africa, I am interested in a broad range of experimental questions relating to:

- quantifying variation in different core reduction strategies

- the origins and development of projectile technology, especially specialized hunting strategies like those of the recent Waata Oromo (Waliangulu).

- the origins and persistence of microlithic technologies around the world

- identifying learning and novices in the archaeological record

Backed crescent function in SW Kenya

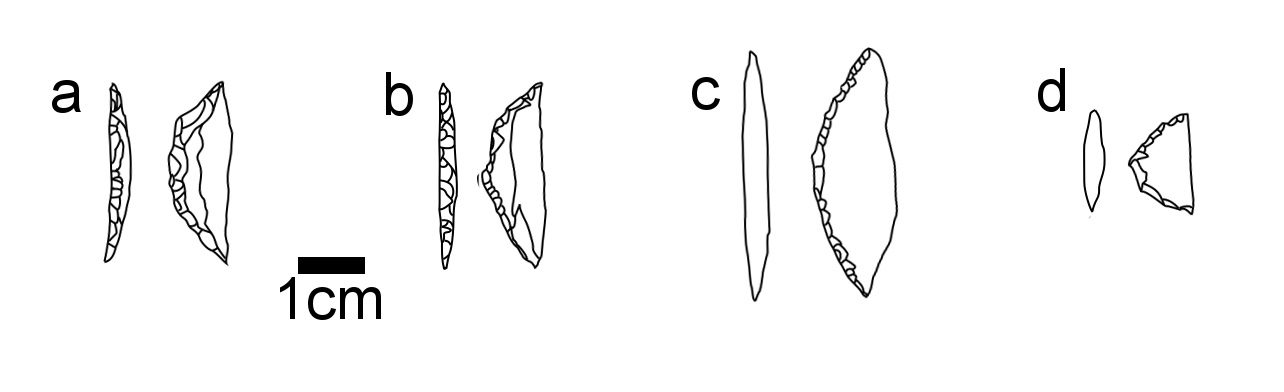

Use of crescents in arrows and composite knives

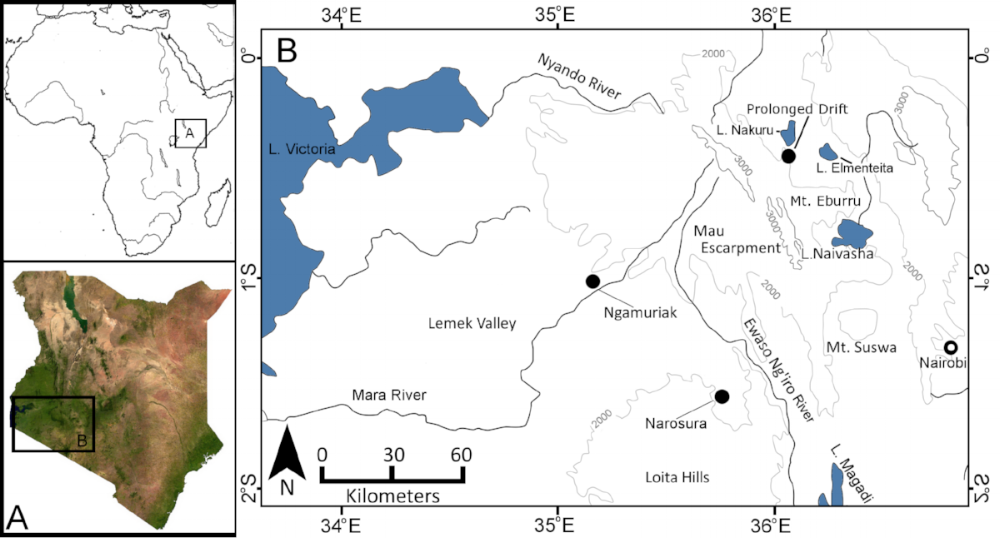

Pastoralist sites in southwestern Kenya with large assemblages of backed crescents. (Goldstein and Shaffer 2017).

Two groups of early cattle herders in southern Kenya both relied heavily on backed crescents from obsidian. The "Elmenteitan" culture consistently manufactured small crescents, whereas the "Savanna Pastoral Neolithic" group made longer and thicker crescents. Fauna from the Elmenteitan site of Ngamuriak , the SPN site of Narosura, and the mixed PN site of Prolonged Drift all have large assemblages of crescents and similar economies within similar environmental conditions. What is the reason for this variation? To find out, I replicated backed crescents matching Elmenteitan and SPN metrics, and hafted them within composite arrows and knives. Knives were used to butcher an adult pig and an adult deer, and the arrows were fired at a target of cow hide over ribs and ballistic gel. We recorded the performance of different sized microliths and the types of damage that crescents accrued during use. I then compared the experimental damage to damage patterns observed on archaeological assemblages from the above sites to determine if there were clear differences in how Elmenteitan and SPN groups were using backed crescents.

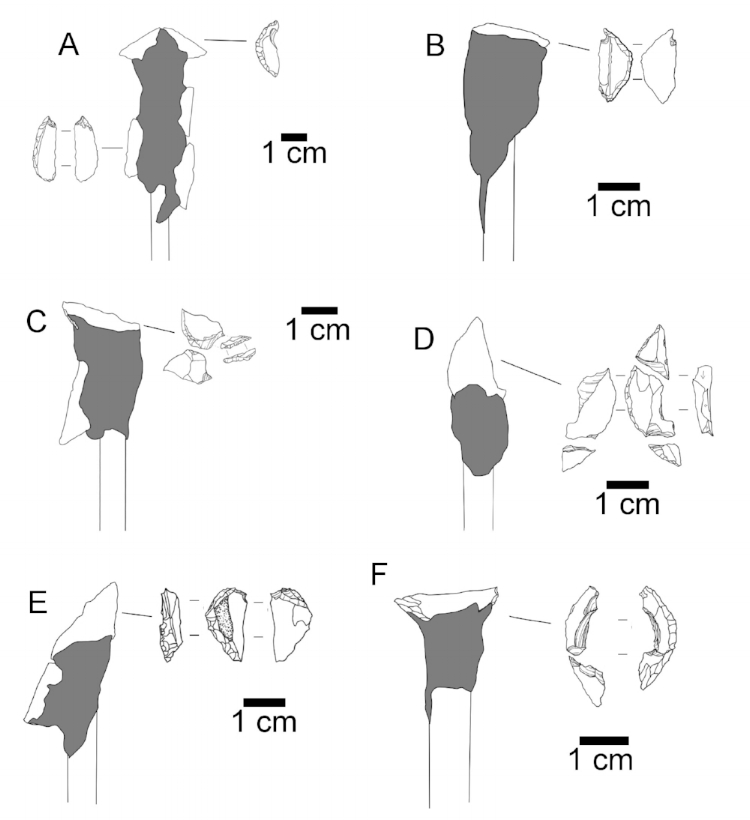

Examples of obsidian crescents hafted onto arrows at different orientations. Projectile experiments showed while (a) and (b) penetrated deeper on average, obliquely oriented pieces (d) was the most resistant to damage, even sometimes breaking bone without showing evidence of damage (see below).

Crescents and interpersonal violence

This archaeological human vertebra from Porcupine Cave in Kenya has a crescent embedded into it from an arrow. This proves microliths were definitely placed obliquely in arrows, at least occasionally used in violence within or between communities. Despite being embedded into bone, this obsidian crescent has no visible damage.

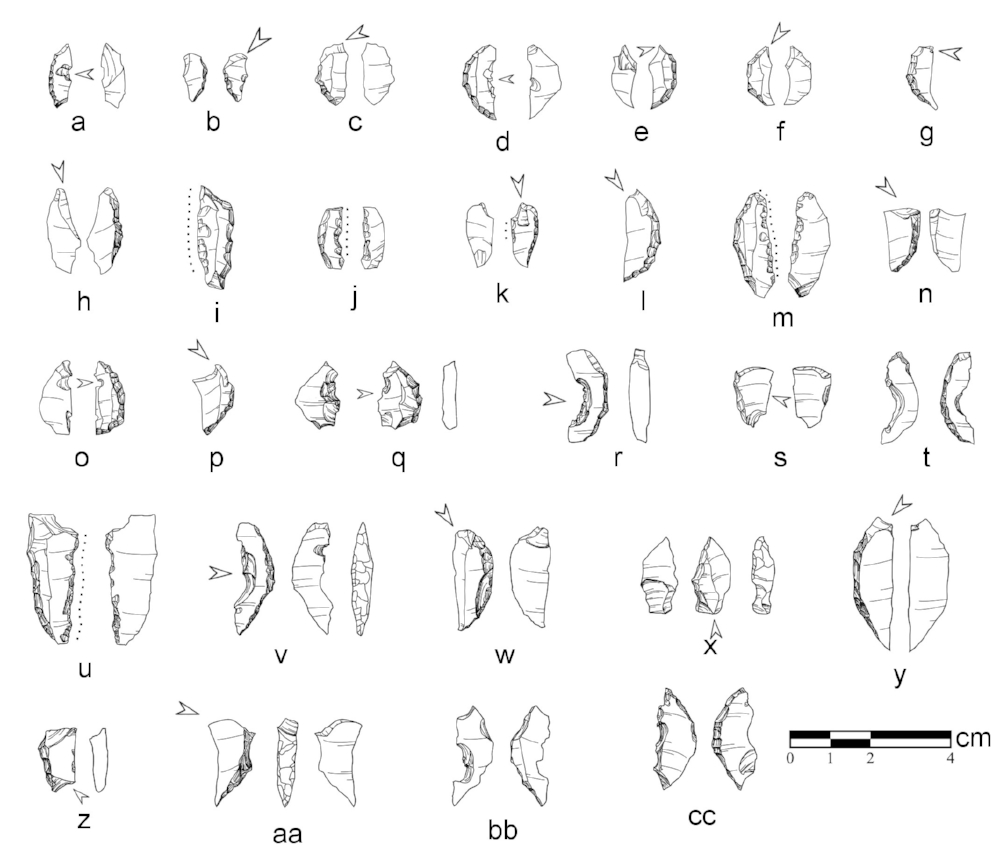

Examples of crescent damage from use in arrows.

Examples of edge damage and probable impact fracture on archaeological microliths from PN sites.

Results

Projectile experiments show that the smaller Elmenteitan style microliths, when hafted obliquely, are the most reliable and damage-resistant form for use in arrows. These are also more consistent in weight and size, providing more predictable arrow firing. The macroscopic impact fracture (microburinations, spin-off fractures) patterns observed during arrow experiments were very different from the edge wear observed from use as knives. Use as cutting edges was easier to identify though. Obsidian microliths proved to be either highly resistant to damage, or would "explode" on impact. Many incurred minor damage (like f,g,l above) that can not be definitely differentiated from trampling (most likely aa, bb, cc above) or other damage. Only a small number of pieces had multiple signs of impact fracture (like a, k, q, v) that are more likely to have resulted from use as arrow tips or barbs.

Compared to archaeological specimens- it is clear that the Elmenteitan site of Ngamuriak and the mixed PN site of Prolonged Drift (with more evidence for hunting) had higher rates of impact fracture. The SPN site of Narosura had more evidence of use of crescents as cutting tools (i, m, u, above). It is possible that arrow technology was more important for the Elmenteitan economy than for the SPN. While both groups made crescents, they were anticipating different needs across the landscape, suggesting different strategies and lifeways between these herder communities. Even with a functional basis for variation between the SPN and Elmenteitan microlith forms, it is likely that they became markers of group identity as these communities interacted in southwestern Kenya. The published results of this project can be found HERE.

I am continuing to conduct experiments with microlith styles of hunter-gatherers to see how they differ from herder assemblages.